By Ellis Farrar and April Grossman

Economic impact reports often leave you with more questions than answers. The Euston Station Regeneration will deliver £41bn to the UK economy by 2053, create 34,000 new jobs, and provide the opportunity to build 2,500 new homes. Seriously impressive numbers. But what do they mean? This blog, written by our colleagues Ellis Farrar and April Grossman, adds colour to the opportunity for Euston Station’s regeneration to transform the area and wider London economy, whilst grappling with crucial questions on inclusive growth.

Understanding the opportunity at Euston

The location of the future London terminus of High-Speed Two (HS2) has been a point of contention. As part of the Government’s approach to controlling costs, the withdrawal of funding for Euston station has led its construction to be framed as a fiscal irritant, a cost problem to be alleviated through watered down delivery of a minimum viable product. Clearly, building a tunnel through a large corridor of central London is going to require significant public investment. But (as can often be the case with capital expenditure in Britain) the opportunity here seems to have been buried underneath short termism, doubt and caution. And while some attention has been afforded to the benefits of connecting London to Birmingham and easing rail capacity elsewhere, less has been paid to the Euston Station regeneration.

We found that Euston Station regeneration has the makings of a genuinely transformative regeneration project. The current experience of Euston is an early-morning fever dream of unpleasant commuting transience. Once you escape the immediate concourse, you’re greeted with a makeshift and cramped public square, consisting of a limited amount of on-the-go food and drink retail, almost no modern office units nor any cultural or leisure amenities, and an obstacle course of scaffolding and wiring leading to a vast construction site round the side and back. In sum, Euston is not actually a place. The station regeneration project provides the opportunity to bring together several under-utilised sites into a coherent economic and cultural hub that functions together as much more than the sum of its parts. Not only will it boost infrastructure capacity, but it will shape new patterns of economic geography driven by a strengthening of agglomeration effects around London’s Knowledge Quarter. It will fundamentally alter the urban fabric of the area, forming connections within and outside it in new ways, such that a future newcomer would find it impossible to imagine how things used to be.

This is the lens from which we view this transformation. An opportunity to bring Euston out from the shadows, on to the centre stage of London, boosted by, but far from limited to, the future HS2 terminus. It is the last major station regeneration project in central London, following on from the successes of King’s Cross, Paddington, and Waterloo. With safety concerns over the current station, a slowdown of economic productivity in London, and a burgeoning cluster of knowledge-based future-focussed firms based around the Knowledge Quarter, it’s the opportunity cost of not pursuing this transformative regeneration that decision-makers should weigh up.

London’s economic geography is shifting towards the Knowledge Quarter. Euston has the chance to play a central role in this shift.

Sometimes referred to as the ‘New Square Mile’, the Knowledge Quarter consists of the one-mile radius around King’s Cross and Euston, featuring a unique combination of institutions shaping the future of the UK and the global economy. The map below helps visualise the mass of innovation powerhouses, high-tech firms, leading academic and research institutions, and cultural attractions which make it difficult to overstate the significance of the Knowledge Quarter.

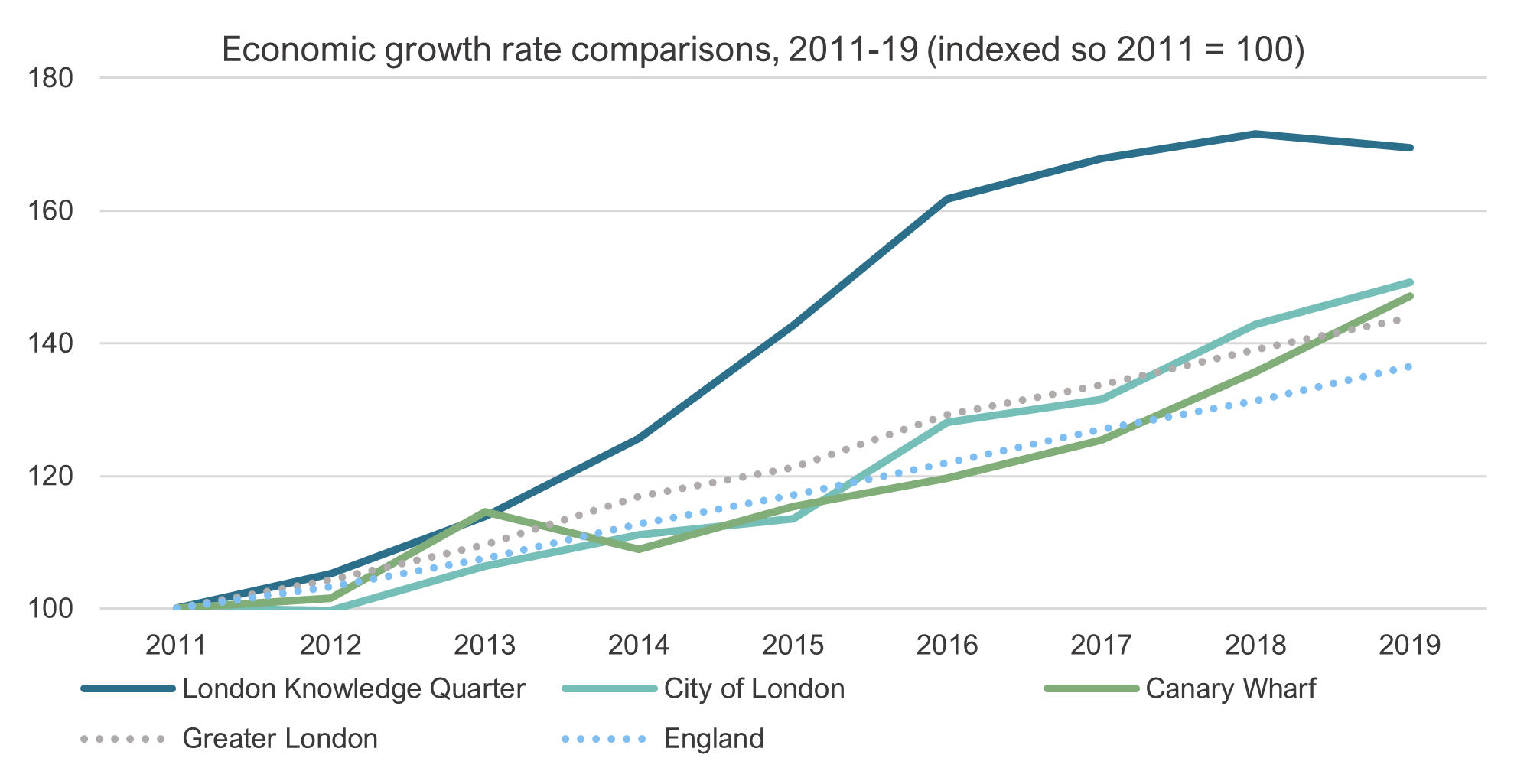

The economic force of the area is disrupting London’s economic geography; the Capital is typically known for its long-established sectors - the powerhouse finance hubs of both Canary Wharf and the City. But this is changing. From 2011-19, productivity growth and economic output growth in the Knowledge Quarter increased at 25% and 70% respectively, compared with 3% and 49% in the City and 3% and 47% in Canary Wharf. The economic centre of gravity in London is moving away from traditional centres towards the King’s Cross and Euston area.

Driven by these forces, this area is quickly becoming more important to the UK economy than anywhere else. The Knowledge Quarter contributed £34bn to the UK’s GVA in 2021, a larger contribution than many entire cities, including Cambridge or Oxford. Growth is set to continue as the area further develops and attracts new major assets, including a major expansion of the British Library, and MSD’s (or Merck in the U.S.) new Discovery Research Centre.

Growth in the Knowledge Quarter could be what London needs to re-establish it’s international competitiveness. According to Centre for Cities, London is responsible for nearly half of the UK’s post-2007 productivity gap, with London since failing to perform in line with its global peers, such as New York, Paris, Stockholm and Brussels. The intellectual and cultural power rooted in the Knowledge Quarter make it highly attractive to growing firms in knowledge-based clusters, which stand to benefit from proximity to similar businesses and access to the best talent, drawn internationally to London.

Development at Euston is bolstering this growth, by addressing the severe shortage of real estate space to accommodate current and predicted demand for life sciences and technology businesses in the Knowledge Quarter, particularly the acute shortage for laboratory space. With low vacancy rates and increasing rental prices in the area, the strength of demand for space in the cluster is clear – now, this demand must be addressed.

The question then becomes – where next for the Knowledge Quarter? Does it have the potential to reach, or even surpass, levels of global dominance seen, for example, in Kendall Square? How does it get there? And how can it take local communities along for the journey?

Euston has some of central London’s most deprived communities on its doorstep - concerted action is needed to deliver sustained inclusive growth at Euston.

Embedding inclusive growth into delivery at Euston will involve a deliberate effort on behalf of those interested in genuinely delivering better outcomes for local people. With public sector coffers currently highly constrained, private investment is an inevitable part of the solution. Indeed, private finance has played a crucial part of major infrastructure projects in London going back hundreds of years, contributing to our inherited system of roads, bridges and underground tunnels. The connection of London to the rest of England via HS2 and complete makeover of the area surrounding Euston Station would be a welcome dose of growth to our stagnating economy. But if the development is left entirely to the market, existing residents in local communities may be left out.

This necessitates conscious, and well thought-out decisions on how to extend the benefits of development to local people, as that’s not something which necessarily comes about naturally in the presence of significant private development finance. There are cases of very successful developer-led placemaking in London – as well as other, far more exclusive and lifeless residential development elsewhere in the city. Turning Euston in to a well-functioning place is a priority, but not the lone measure of success. Regeneration here should also be judged on its impact on the communities nearby, some of inner-London’s most deprived, which see higher rates of child poverty, lower wages and skills levels, and high housing costs.

Delivering on inclusive growth ambitions at Euston, requires much thought on how to incentivise the private sector to do right by Euston’s residents. This will have to go beyond public consultation and community engagement, to consider how to ensure local communities are able to continue to live in the Euston area, fill local job vacancies, and make use of new public spaces and community assets. Balancing transformative upgrades to national transportation, alongside a public realm overhaul to host a major economic hub, all whilst providing positive outcomes to local residents is a complicated matter. Indeed, that’s the nature of ensuring economic growth in our capital city is accessible to all. But it can be done. Given that Camden Council is committed to inclusive growth at the site, regeneration at Euston Station has the potential to be an exemplar for how to drive successful, genuine, locally-led regeneration. Let’s hope this potential can be fully realised.