Amidst all the discussion surrounding the newly released deprivation data for England, one finding stands out – wherever you are, there are clear correlations between the different “domains” of deprivation. For instance, consider the link between health deprivation and income deprivation. Of the areas in the bottom decile for health deprivation (Figure 1.), 89% are in one of the bottom two deciles for income deprivation. This works both ways – of places in the bottom decile for income deprivation (Figure 2.), 87% are in the worst fifth for health deprivation.

Source: Metro Dynamics analysis of MHCLG Index of Multiple Deprivation data (2019)

There are many links between the two. Income poverty can be detrimental to health through channels such as poor housing, resources to fund a healthy diet and harmful living environments. The outcome of poor health can in turn hinder an individual’s ability to secure good work and progress within the workplace. A negative feedback loop emerges where people become trapped in a cycle of poor health and poverty. This can pose an immense barrier to inclusive growth.

The economic consequences of poor health are borne by the whole of society, with a staggering 140 million working days lost to sickness absence each year.[1]

This is not news – policy makers have been aware of the challenges and costs of poor health for a long time. But to date, most of the government’s response has taken the form of policies which aim to encourage behaviour change; implementing programmes to encourage healthy eating, physical exercise and smoking cessation.

The missing ingredient: workplace environment

These policies are critical, but on their own are inadequate because they focus only on what people do with a small section of their day – exercise is a leisure activity and most eating takes place outside of working hours. But much of an individual’s time spent awake is at work. Not only does work life have a large impact on health, poor behavioural habits are often found at the end of a long chain of causes. For example, a stressful work environment may induce unhealthy coping mechanisms from an employee such as alcohol consumption and poor eating. Around 27 million of the days lost to sickness absence are work environment related, 10.4 million of which are down to work-related stress, depression or anxiety[2]. In these cases, policies would see greater returns by attacking the roots of the problem, at the workplace, rather than the symptoms.

How does a poor working environment impact health?

A growing body of research focuses on the “psychosocial factors” which affect an individual’s experience of their workplace. These are the social conditions of daily life that act through the mind to affect wellbeing and health. For example, stress is an integral concept in understanding psychosocial factors on health. Psychological stress over a persistent period of time can induce mental health and stress related illness such as heart disease and diabetes.

Stress at work and its impact on health has been extensively researched with regards to the psychosocial pathway mediated by stress. Two theoretical models of work stress have been developed which include the “demand-control” model[3] and the “effort reward imbalance” model[4]. The demand-control model proposes that jobs with high employer demand and low control over work induce stress, which negatively impacts the health of the employee. And the effort-reward imbalance model captures work related stress through a lack of fairness of efforts in exchange for rewards received. When rewards (in the form of money, esteem and opportunities) are not deemed equitable by the employee i.e. low reward, high effort, it generates employee stress.

Lower income groups face the brunt of the problem

The next question to ask is: are those in lower income groups more exposed to a poor working environment with regards to these mechanisms? Does this go some way to explaining the relationship between income and health poverty?

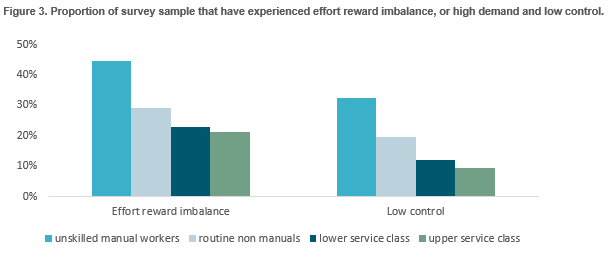

The 2012 Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe provides robust evidence in support of this. 6 In the survey, occupation is broken down into four different categories, very high (upper service class), high (lower service class), low (routine non-manuals), very low (unskilled manual workers).

They find that the proportion of individuals in the sample experiencing effort reward imbalance was 21.1% among those with “very high” occupational class, but more than double – 44.5% - among those with “very low” occupational class. The proportion experiencing low control was 9.3% in very high occupational class and 32.6% of those with very low occupational class. This strongly supports the idea that the work environment contributes in explaining why the poorest have the worst health.

How can policy address the issue?

Policies should move beyond just encouraging healthier behaviour and have a greater focus on the psychosocial work environment. Initiatives taken by policymakers should be designed with the two stress models in mind, aiming to increase employee control over their work through strengthening decision making and to improve the reward structure for employees.

In some places around the UK, this kind of approach is already taking effect. For example, Greater Manchester Combined Authority in the hopes of narrowing the 4-year disparity in life expectancy against the national average has developed an employment charter that involves supporting employers to reach best practice, through enabling secure and flexible work, workplace engagement and voice and a healthier workplace.

With the rise of the gig economy, the number of insecure jobs in Greater Manchester has proliferated, with over 30,000 zero-hour contract jobs based here [5]The charter works to promote greater employee clarity on the number of hours that are worked and reduce the forms of insecure work. This will give employees more control over their income and time spent working, which should reduce the stress of employees.

From a wider perspective, Public Health England has identified the role of the work environment in improving mental health within its 2020-25 strategy. They aim to work with employers to help them better understand the role they play in the mental health of their employees along with improving access to secure employment opportunities to those with mental health problems [6].

PHE also highlights the opportunity of using digital technology to collect greater personal data which will help identify health problems earlier on and provide more tailored advice and support. Greater data on individuals regarding occupation and stress levels, could aid in our understanding of what types of workplace are more prone to stress, and facilitate more personalized interventions such as stress management to those in occupations with poorer working environments.

Whilst action to address the work environment is slowly being made at the local and national level, there is still a lot more scope for intervention to take place, with the costs of work related illness in the UK remaining high. If we want to tackle deprivation and deliver inclusive growth, these environments must be a priority.

[1] Black C, Frost D. Health at work - an independent review of sickness absence. London: 2011.

[2] Health and Safety Executive. Working days lost 2014.

3 Siegrist, J., Starke, S., Chandola, T., Godin, I., Marmot, M., Niedhammer, I., et al. (2004). The measurement of effort-reward imbalance at work: European comparisons.

4 Karasek, R. A. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain - implications for job redesign. Adm. Sci. Q. 24, 285–308.

5 Wahrendorf, Morten & Dragano, Nico & Siegrist, Johannes. (2012). Social Position, Work Stress, and Retirement Intentions: A Study with Older Employees from 11 European Countries. European Sociological Review.

6 Greater Manchester Combined Authority: GM good employer charter evidence paper (2018)